|

THEPITCAIRN ISLAND

|

PREFACEThe S.P.C.K. and myself have been singularly fortunate in securing in regard to the present work the active cooperation of Sir Everard im Thurn, K.C.M.G., K.B.E., C.B., who, after retirement from six years' tenure of the Government of Fiji and the High Commissionership for the Western Pacific, has up to the present day devoted himself to the study of the Pacific, its history, problems and races, and to forming a collection of rare books and pamphlets connected with it. Every part of the present volume has been revised by him, including the map, based upon a map drawn specially for a lecture which he gave some years ago before the Royal Geographical Society, and the Second Appendix is entirely his handiwork. The S.P.C.K. were good enough to place at my disposal as private secretary and typist for the purpose of this work the willing and competent services of Miss Ethel Young. I am greatly indebted to her for making necessary researches which I was not well enough to carry out myself and, as noted at the beginning of my Introduction, two of the three Appendices are, in addition to the Index, in whole or part due to her. It should be added that the present book is intended to be the first of a series of S.P.C.K. records. The Society possesses archives of considerable interest and value, which it is hoped to publish in due course. C. P. Lucas.

January 1929.

|

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

|

THE PITCAIRN ISLAND

|

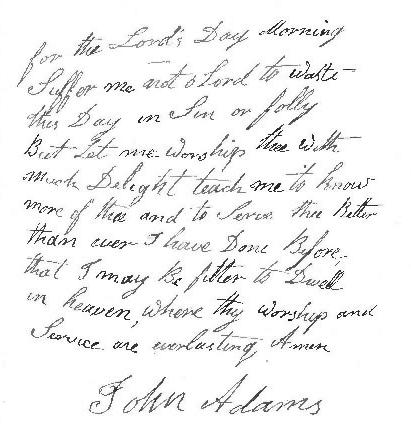

of the Society. It has already appeared in Pitcairn, the Island, the People and the Pastor, with the following note: "facsimile of a prayer in the handwriting of John Adams, the original of which was presented by his grandson Mr. John Adams of Norfolk Island to the Revd. T. B. Murray." It must be repeated that the glaring mistakes and inconsistencies which will at once strike the eye in the Register and shipping entries are not typist's errors or due to want of revision. They represent as nearly as may be the original. Anything that is not in the original is given in square brackets, sic [ ]. Besides the Register Book, this volume contains a map of the Pacific Ocean giving the principal places mentioned, and an index of principal places and persons. There are also three Appendices; one – compiled by Miss Ethel Young – containing a note on three small volumes of the Proceedings of the Pitcairn Island Fund Committee and the connected correspondence which are in the possession of the Society; a second – by Sir Everard im Thurn – giving a short account of the Pacific whale fishery which brought so many New England whaleships to Pitcairn Island; and a third – compiled by Miss Young and revised by Sir E. im Thurn giving a bibliography of publications relating to Pitcairn Island up to the date of the removal to Norfolk Island. The Mutiny of the Bounty and its outcome, the settlement on Pitcairn Island, was a fruitful theme for writers in the nineteenth century. Lieutenant, afterwards Admiral, William Bligh had served with Captain Cook on his second voyage of discovery in 1772-5, and with him had visited Tahiti, then known as Otaheite, in the Society Islands, where they became familiar with the Bread-fruit. Bligh seems to have been a most competent sailor, and a man of exceptional courage and resolution; he attained much distinction in the Royal Navy; but twice in his career he was the subject of and deposed by a mutiny on sea when he commanded the Bounty, and on land at a later date when he was Governor of New South Wales. Captain Cook suggested the introduction of the Breadfruit into the West Indies, and the records of the West India Committee show that, in and about the years 1775-6, |

the project was taken up warmly by the West Indian planters and merchants, who saw in it the promise of a cheap food supply for their slaves. They offered rewards for successful importation of Bread-fruit plants into the West Indian Islands, and secured the powerful advocacy and support of Sir Joseph Banks, with the result that eventually the Government decided to act, and Bligh was selected to command a ship, the Bounty, an "armed transport" of nearly 215 tons, intended to visit Tahiti, collect the plants and carry them on to the West Indies. The complement of the ship was 44, including Bligh himself, and in addition there was a botanist or gardener, with an assistant, chosen by Sir Joseph Banks to take charge of the plants. There were thus 46 persons in all on board. A start was made from Spithead on the 23rd of December 1787, just a month, it may be noted, before Phillip arrived at Port Jackson with the first English settlers for Australia and founded Sydney. Tahiti was reached – via the Cape and Tasmania, not as had been intended via Cape Horn – on the 26th of October 1788. One sailor died on the voyage, and the surgeon, a confirmed drunkard, died after the ship had arrived at Tahiti. The numbers on board were thus reduced to 44. Twenty-three weeks were spent at Tahiti. The ship left on the 4th of April 1789, and at dawn on the 28th of April 1789, when she was in the neighbourhood of Tofoa among the Friendly Islands, afterwards known as the Tongan Islands, a mutiny took place. Bligh with 18 others was cast adrift in a small boat, which after great sufferings was by his indomitable courage and tenacity brought to the island of Timor in the East Indian Archipelago. Twelve out of the nineteen lived to reach England in safety. Bligh himself landed at Portsmouth on the l4th of March 1790, and the Government lost no time in sending out a frigate, the Pandora, commanded by Captain Edwards, to follow up the mutineers and bring them back to England for trial. Twenty-five had remained on board the Bounty out of the forty-four, and they were, according to Bligh, "the most able men of the ship's company." After attempting to settle in the Tubuai islands due south of Tahiti, but being prevented by the hostility of the natives, they returned to Tahiti; they then |

made a second attempt to settle in Tubuai, and again went back to Tahiti. Here there was a further division of numbers. Sixteen out of the twenty-five stayed there or were left behind. Two of them were killed, one by the other, and the murderer by the natives: the other fourteen surrendered or were rounded up by the Pandora, which reached Tahiti on the 23rd of March 1791, after visiting and naming Ducie Island – thus passing close by Pitcairn. The prisoners seem to have been treated on board the Pandora with gross inhumanity, being heavily chained and kept in a kind of cage. The Pandora was wrecked on the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef, just east of Torres Straits, and four out of the fourteen were drowned. The other ten were brought home and placed on trial, with the result that three were executed, four were acquitted, and three were pardoned. Among those who were pardoned was a lad, Peter Heywood, who had been detained on the Bounty against his will and whose case excited much sympathy and interest. He subsequently rose high in the Royal Navy. A memoir of him, with extracts from his diaries and correspondence, was written by the Unitarian divine, Edward Tagart; there is also an account of him in the Dictionary of National Biography; and an earlier account, which will be found under the category of the post captains of 1803 in Marshall's Naval Biography, Vol. II, Part II, 1825, is a very valuable source of information on the mutiny of the Bounty. There were still nine mutineers to be accounted for; the Pandora sought for them in vain, and nothing was heard of them for years. The leader of the nine, Fletcher Christian, had been the leader of the mutiny. In the original crew of the Bounty he had been a master's mate, but had been much trusted by Bligh and promoted by him to be an acting lieutenant. Bligh described him as "of a respectable family in the north of England," and he was clearly of better standing and education and of stronger will than the rank and file of his shipmates. An account of him, as also of a brother of his who attained some celebrity at Cambridge and as a jurist, will be found in the Dictionary of National Biography. The other eight were Edward Young, one of the midshipmen, also better connected than the average Bounty seaman, William |

Brown, William McCoy, Isaac Martin, John Mills, Matthew Quintal, John Williams, Alexander Smith. Of them Brown was the assistant gardener and Mills was a gunner's mate, while the other five were ordinary seamen. Alexander Smith, when found on Pitcairn Island – the last survivor of the nine – came to be known as John Adams, no longer a mutineer but the patriarch and central figure of a deeply religious and highly moral little community. He had registered for service in the Bounty as Alexander Smith, but whether that name or John Adams, or neither, was his real name is uncertain. He was Alexander Smith when the Topaz called at Pitcairn in 1808, but John Adams when the Briton and the Tagus called in 1814, and it is suggested by the American writer Amasa Delano, in his Narrative of Voyages and Travels, that the call of the Boston ship Topaz, and conversation with her New England captain, Folger, may have induced Smith to change his name for one with American associations and to choose the name of John Adams, the well-known New England President of the United States. Delano and Captain Mayhew Folger were personal friends. At any rate, as John Adams the central figure of Pitcairn takes his place in the story and in the Dictionary of National Biography. The writer of the article in the Dictionary, Sir John Laughton, reasoned that he must have had an exceptional education, but this supposition is inconsistent not only with other accounts but also with Adams' handwriting, which, as the facsimile shows, was that of an uneducated man. With these nine Englishmen went nine Tahitian wives, three Tahitian men and their wives, three Tahitian men without women and one infant girl. Christian, according to the story, having read on the Bounty of Philip Carteret's discovery of Pitcairn Island in 1767, sailed in search of it, and found it at the beginning of 1790. The first item in the Island Register is "1790 January 23 H.M. Ship Bounty burned at Pitcairn Island." Thus the mutineers literally burned their boats – not, however, for the purpose of making retreat impossible, but in order to conceal their identity. Pitcairn Island in the Eastern Pacific, called after a boy on Carteret's ship who first sighted it, is just south of the Southern tropic. It is nearer to South America than to Australia, and in the same latitude as the north of Chile. |

The Pitcairners' communications with the mainland in the Pacific were not with Australia so much as with South America, especially with Valparaiso. The island lies southeast of Tahiti, and about 100 miles south of the nearest island of the Tuamotu or Low Islands group. Its area is two square miles, and it is a very high island girded with steep cliffs, in the words of Sir Thomas Staines' despatch "completely iron bound with rocky shores." What happened after the arrival of the mutineers in the island until intercourse with the world was resumed must have been gathered subsequently. When, in December 1825, Captain Beechey in H.M.S. Blossom called at Pitcairn, John Adams gave him his story, which will be found in the "Narrative of a Voyage to the Pacific and Beering Strait to co-operate with the Polar Expeditions: performed in His Majesty's Ship Blossom under the command of Captain F. W. Beechey, R.N.; F.R.S.; F.R.A.S.; F.R.G.S.; in the years 1825, 26, 27, 28. Published by authority of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, 1831." Beechey writes: "The following account is compiled almost entirely from Adams' narrative, signed with his own hand, of which the following is a facsimile. But to render the narrative the more complete I have added such additional facts as were derived from the inhabitants who were perfectly acquainted with every incident connected with the transaction, they having derived their information from their parents." In 1823 John Buffett and John Evans came to live on the island, the first two white men to join the original settlers, and Buffett made a beginning of the Island Register. John Adams died in 1829. Among the publications in the middle of the last century which treat of the mutiny and of Pitcairn Island was one fathered by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. It was entitled Pitcairn, the Island, the People and the Pastor. The first two editions appeared in 1853, and the Preface to the twelfth edition, which was published in 1860, stated that by that date about 30,000 copies had been printed. In September 1860 the writer of the book died. He was the Rev. T. B. Murray, who had been appointed assistant secretary of the Society in 1835, and promoted to be one of the four joint secretaries in 1842. |

After his death the book was re-issued and brought up to date from time to time, the latest edition being dated 1909. While Murray lived, he was the main representative of the Society in all its dealings with the Pitcairn Islanders, and as such formed a great friendship with the Rev. G. H. Nobbs, who, after the death of John Adams, gradually became the central figure in the Pitcairn community. A notice of Mr. Nobbs, written by Sir John Laughton, will be found in the Dictionary of National Biography. His parents' names are not stated, and it was at his mother's wish that he took the name of Nobbs. He was born in 1799 and died in 1884. As a boy he was sent into the Royal Navy and went on a voyage to Australia. He left the King's service to take part with the South American patriots in their fight for independence, and subsequently, among other voyages, he twice went to Sierra Leone. Possibly the record of evangelical philanthropy connected with the founding of the colony of Sierra Leone which, it is worth noting, was contemporaneous with the voyage of the Bounty, may have inspired him to look around for similar work. At any rate, he had been told of and attracted by the account of the settlement on Pitcairn Island, and he seems to have left England in 1826 with the object of going to Pitcairn, tried in vain to find his way there for the better part of two years, and eventually reached the island from Callao in Peru in a launch with a single companion, who died soon after arrival. Nobbs landed on the 5th of November 1828, and John Adams died four months later; Nobbs in due course carried on his work. In 1839 Nobbs took over the Island Register, which Buffett had kept up to that date, and greatly expanded it. In August 1852, through Admiral Moresby's good offices, he went to England to be ordained a clergyman of the Church of England, and it is interesting to read that he was ordained deacon at Islington by a Bishop of Sierra Leone in October 1852, prior to receiving in the following month priest's orders at the hands of the Bishop of London. Before he left England he was accredited a missionary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, with a small salary, and he reached Pitcairn again on the 15th of May 1853. His place during his nine months' absence had been taken by the Rev. W. H. Holman, the Chaplain of Admiral |

Moresby's flagship, who was the first to administer the Holy Communion on Pitcairn Island. Under Mr. Holman (as appears from the Minutes of the Pitcairn Island Fund Committee) John Arthur, son of the master-at-arms on board the Admiral's ship, took charge of the school, also remaining on the island while Mr. Nobbs was away. He had fifty scholars under his care. The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge had been to some extent in touch with Pitcairn ever since 1819, when the Records of the Society state that a first gift of books was sent there by their Diocesan Committee at Calcutta. After Nobbs settled in the island and Murray had joined the secretarial staff of the Society, the two men corresponded with each other, and when Nobbs came to England to be ordained in 1852, Murray took charge of him and presented him for ordination. Thus he became the recipient from Nobbs of the Island Register Book, when the original book was discarded in 1854 on account of its dilapidated condition. It was evidently intended in the beginning to be a register in the ordinary sense, a register, as the heading of the first page states, of "Births, Deaths, Marriages and Remarkable Family Events," and Buffett dealt sparingly with other matters. Thus of the murderous year 1793 the record is studiously vague, the terms being "Massacre of part of the mutineers by the Tahitians. The Tahiti men all killed, part by jealousies among themselves, the others by the remaining Englishmen. Mary Christian born." In the entry for the first year, 1790, is recorded "Same year died Fasto wife of John Williams," and the standard story is that John Williams, having lost his wife, replaced her with the wife of one of the Tahitian men, that this outrage and the general treatment of the coloured men by the whites led to a rising of the Tahitian men and the murders and reprisals of 1793. After this date only four white men are mentioned, the other five having been killed by the Tahitians, and Fletcher Christian being one of the five. The various books give a story that Christian returned to England and lived and died in concealment, that about 1809 he or his double was seen by Peter Heywood in the streets of Plymouth or Devonport, and that the man in question, when Heywood spoke to him by name, immediately ran away. Sir John Laughton in his article in the |

Dictionary gives his opinion to the effect that Heywood could hardly have been mistaken and that it was in high degree probable that Christian found his way home; but his reasoning does not carry conviction; the accounts seem perfectly clear as to Christian having been one of the five Englishmen who were murdered by the Tahitians in 1793, and evidently Nobbs had no doubt that he was killed on the island, as shown by the lines which are prefixed to the Register. John Adams is stated to have been badly wounded, but to have been called back by the Tahitians when he was running away, with the promise that his life would he spared. Then the surviving white men with the widows of the murdered whites killed the six Tahitians, or those of them who had not been killed by their fellows, and the ghastly year ended with only four male adults left on the island. It is not surprising to read in the entry for the following year, 1794, that some of the Tahitian women wished to leave a scene of so much crime; hut the Register makes no mention of plots to kill the four white men which these women are said to have made, but which were discovered before they could be carried out. All four of the remaining white men survived till 1798, when McCoy in a fit of drunken delirium threw himself into the sea and was drowned. His drunkenness with its fatal consequence can only, it would seem, have been achieved by converting an old boiler of the Bounty into a still and thus procuring an intoxicant from the Ti root. Ti is the Polynesian name for one or more species of the plants which are known in this country as dracaenas and which are used for various purposes by the natives of the Pacific Islands, including in some islands, according to the authorities on the subject, extraction of intoxicating liquor from their tuberous roots. In the following year, 1799, Quintal, having threatened and attempted the lives of Young and Adams, was killed by them in self-defence. In 1800 Young died a natural death, leaving Adams the solitary survivor of the original nine. It is difficult to understand the list of births from 1794 to 1799 inclusive, as entered in the Register under 1799, and especially difficult to account for the fact of seven out of the total number of children bearing the name of Young. An entry in the Register will be noted under date 27th of December 1795 to the effect that the mutineers were |

greatly alarmed at seeing a ship close in to the island, and another account states that in May of that year at the sight of a ship nearing the island they hid themselves and subsequently found that there had actually been a landing on the beach. But that the island was inhabited was not discovered till 1808. The entry for that year includes "Arrived Ship Topaz of Boston Captn Folger." The curtain is now drawn back and the light of day let in upon this singular little colony which had grown up unknown to the world for between eighteen and nineteen years. Its existence was reported by the commander of the Topaz, but very little notice was taken at the time, because there was so much else to divert attention. Curiously enough, this year 1808 was the year in which Bligh, who had become Governor of New South Wales in 1806, experienced his second mutiny and deposition. Happily there was no such tragic sequel on the later as on the earlier occasion. In order fully to appreciate the Pitcairn story, it is necessary to keep before the mind's eye the contrasts which it presented. What could be more remote from the murders and crimes of the early years upon the island than the settlement as it developed under John Adams, in peace, godliness and comparative innocence? Or, again, contrast the day-to-day life of this tiny isolated group of human beings, as it flowed on in even monotony, with the wars and rumours of wars and great events which in the same years stirred the whole outside world. Pitcairn might have been in another planet. In 1805, three years before the Topaz called at the island, Trafalgar had been fought and won, but the British fleet were still in demand off every land and in every sea. In 1808 the Peninsular War had begun, and there had been a beginning too of friction between Great Britain and the United States which in 1812 brought about the second war between the two nations. In that war powerful American frigates, admirably handled, achieved many successes against individual British ships, and in the Pacific one of those frigates, the Essex, commanded by David Porter, for many months harassed British shipping, captured British whalers and gained great fame. Under these conditions it is not surprising that there were, as far as can be gathered, no more calls at Pitcairn until, after an interval of six years, the Register records the |

arrival at the Island on the 17th of September 1814 of H.M. Ships Briton and Tagus. The Briton frigate, commanded by Sir Thomas Staines, had started from England in December 1813 with a fleet for the East Indies. One of the ships, an East Indiaman, became disabled, and the Briton was told off to take charge of her, thereby becoming separated from the fleet. She brought the East Indiaman to Rio Janeiro on the 20th of March 1814 and left again on the 28th of March, parting company with the East Indiaman and in receipt of instructions to go round Cape Horn instead of the Cape of Good Hope in order to join in the pursuit of the Essex, then reported to be refitting at Valparaiso. She reached that port on the 21st of May and found that the Essex had already been taken by the British ships Phoebe and Cherub, and was being sent as a prize to England. At Valparaiso the Briton was joined by the Tagus, and the two ships went up the coast to Callao, the Port of Lima, visited the Galapagos islands, then turned south to the Marquesas group, where Captain Porter had lorded it over the natives, and were returning to Valparaiso, when they came to Pitcairn Island by accident, not by design, owing to that island having been wrongly charted. "I fell in with an island where none is laid down either in the Admiralty or other charts," wrote Sir Thomas Staines in his despatch. It was a great surprise to find that the island was peopled by English-speaking inhabitants to the number of 40, only eight of whom were original settlers – one man and seven women. Captain Folger had placed the population in 1808 at 34 women and children in addition to Alexander Smith (not yet John Adams). If his figures were correct, 40 was probably an underestimate of the numbers in 1814. By 1814 the mutiny on the Bounty was ancient history, and though John Adams, to the great distress of the islanders, expressed his readiness to go back to England and stand his trial, no attempt was made by the Government to call him to account for what was long past or to interfere with his good work. Three years passed, and then the Register records that in 1817 another ship called, the Sultan, like the Topaz a Boston vessel, a Tahitian woman leaving in her. No further call is recorded till the 10th of December 1823, and then "Arrived ship Cyrus of |

London Capn. Hall and John Buffett came on shore to reside as schoolmaster John Evans also came on shore." Thus two white men were added to the Pitcairn circle, and the names of Buffett and, in a lesser degree, of Evans multiplied in the lists. Buffett had been, like Nobbs, a sea-faring man, serving in British or, more often, American vessels. He had had his fill of dangers and adventure and had been twice wrecked. He must have gone to sea very young, for he was only 27 when, in 1823, the British whaler Cyrus, on which he was serving, brought him to Pitcairn. Then, according to his own account, the Pitcairners being in want of someone to teach them to read and write, and his captain giving him the option of remaining on the island for that purpose, he was discharged, Evans accompanying him, and he became a leader on the island. In the Register, between the visit of the Briton and the Tagus on the 17th of September 1814 and the visit of the Cyrus which brought Buffett and Evans on the l0th of December 1823, only the Sultan is mentioned as having called at the island, but there is abundant evidence from other sources that various ships called. One may be specially mentioned, the American whaleship Russell of New Bedford, commanded by Captain Arthur. This vessel reached Pitcairn on the 8th of March 1822 and stayed there till the 12th, another ship also being at the island at the same time. The following extract from Captain Arthur's Diary is of particular interest. "From all I had otherwise read and learned respecting the inhabitants of Pitcairn's Island, induced me to have the following notice put up in the forepart of the ship, before we had any communication with the islanders. "'It is the impression of the Russell's owners, that the most part of the company were from respectable families, and it is desirable that their conduct towards the islanders should verify the opinion. As the island has been hitherto but little frequented, they will be less susceptable of fraud than a more general intercourse with the world would justify. It is desired that every officer and man will abstain from all licentiousness in word and deed, but will treat them kindly, courteously, and with the strictest good faith. As profane swearing has become an un-fashionable thing even on board a man-of-war, it is quite time |

that it was laid aside by whalemen, particularly at this time. As these islanders have been taught to adore their Maker, and are not accustomed to hear His name blasphemed, they were shocked with horror, when they heard some of the crew of an American ship swear, and said it was against the laws of God, their country, and their conscience.'" Captain Arthur followed up this notice by visiting the Pitcairners in their homes and verifying the high opinion of their religion and morality which he had been led to form. That the captain of an American whaleship should provide such a noble example of regard for godly simplicity is the more noteworthy as at a later date the conduct of the crews of such ships when they landed on the island was in some cases open to grave exception. Reference has been made above to the opening of communications in 1819 between the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Pitcairn through the Calcutta Committee of the Society, and the Annual Report of the Society for 1819 mentions that in July of that year an opportunity had occurred of "communicating with the little colony of Pitcairn's Island in the South Pacific ocean by the departure from Calcutta of the ship Hercules for that place . . . "This is followed by a copy of a letter which the joint Secretary of the Calcutta Committee wrote on the 15th of July to "John Adams and others on Pitcairn's Island," and which begins, "It is with particular pleasure that I take an opportunity of sending to you by Captain Henderson of the ship Hercules a small stock of religious books." The Register contains no mention whatever of the arrival of the Hercules, nor can it be verified from the Society's records, but it appears from the Calcutta Gazette of the 6th of May 1819 that the ship first touched at Pitcairn on her passage from South America to Bengal on the 18th of January 1819, and therefore it was her second visit to the island of which the Calcutta Committee of the Society took advantage, to write to John Adams and send books for the use of the inhabitants. Within comparatively easy distance of Pitcairn is the island, now a dependency of Pitcairn, which bears Captain Henderson's name. It also obtained the alternative name of Elizabeth Island from another ship called the Elizabeth. |

A notice of this island is given in Captain Beechey's book, in which it is stated that both vessels visited it and each captain claimed to have discovered it on his "arrival the next day at Pitcairn Island, these two places lying close together," that the visit of the Hercules preceded that of the Elizabeth by three months, but that as a matter of fact the first discoverers were a boat's crew of survivors from the wreck of the American whaleship Essex (not to be confounded with Captain Porter's more famous ship of war of that name), who landed on the island on the 20th of December 1820, Elizabeth Island is referred to in the Register under the dates 4th of March 1843 and 16th of August and 11th of November 1851. Among the relics of the Bounty in the Royal United Service Institution is what is known as John Adams' Prayer Book, a book of prayers and devotions, though not a Church of England Book of Common Prayer, on the last page of which, apparently written by John Adams himself, are the words "John Adams his book given him by Samuel Henry Rapsey of the ship Elizabeth 5 March A.D. 1819." The Elizabeth therefore called at Pitcairn very shortly after the first call of the Hercules. Captain Beechey was wrong in giving priority in discovery of Henderson Island or Elizabeth Island to the shipwrecked crew of an American whaleship and in dating the first discovery the 20th of December 1820. In the very rare pamphlet entitled "Narrative of the most extraordinary and distressing shipwreck of the whale ship Essex of Nantucket which was attacked and finally distroyed by a large spermaceti whale in the Pacific Ocean; with an account of the unparalelled sufferings of the Captain and crew. . . . in the years 1819-1820, by Owen Chase of Nantucket, first mate of the vessel, New York, 1821," it is stated that the refugees after landing on the island found cut on a tree near their landing place the name Elizabeth, showing that a ship of that name had preceded them, though no date accompanied the name. The conclusion to be drawn is that the Elizabeth reached the island in question before the castaway crew of the Essex, and the Hercules under Captain Henderson before the Elizabeth. After the calls of the Topaz and of the Briton and Tagus, mentions or omissions of ships in the Register, under Buffett's handling, seem to have largely depended on |

whether or not the call affected the family circle. Hence the visit of the Sultan in 1817 is coupled with the entry "Left this Island in the Sultan Jenny a Tahitian woman," and if no one came or left in the Hercules and Elizabeth, that may conceivably be the explanation of their visits being ignored. Under the year 1825 we have the entry "Arrived H.M.S. Blossom, Capn. F. W. Beechey Esq during the stay of the Blossom John Adams married." Thus the arrival of a ship is coupled with a marriage – old Adams, so Beechey tells us, having long wished for the marriage ceremony to be read over himself and his blind, bedridden wife – but probably the call of one of the King's ships would in any case have been chronicled. The entry for 1826 contains "Dec. 19th Jane Quintal left the island in the Brig Lovely Ann of London Cap Blythe." The important point for the purpose of the Register is evidently not that the Lovely Ann called, but that Jane Quintal left in her. In 1830, however, we have a mention of the arrival of one of the King's ships, not linked on to any family event: "March 15th Arrived H.M.S. Seringapatam Capn. Hon. Wm. Waldegrave with a present of cloathing and agricultural tools from the British government." Under 1828 is the entry "George Nobbs came on shore to reside." No ship is named, as we have seen that he is said to have come to the island in a small craft from Callao, and it is also not mentioned that he had a companion, presumably because the latter died soon after arrival. Under 1829 we have "March 5th John Adams died aged 65," and with his death comes the end of the first chapter in the story of Pitcairn Island. Many notable cases of religious conversion have been recorded in the history of Christianity, but it would be difficult to find an exact parallel to that of John Adams. The facts are quite clear. There is no question as to what he was and did after all his shipmates on the island had perished. He had no human guide or counsellor to turn him into the way of righteousness and to make him feel and shoulder responsibility for bringing up a group of boys and girls in the fear of God. He had a Bible and a Prayer Book to be the instruments of his endeavour, so far as education, or rather lack of education, served him. He may well have recalled to mind memories of his own childhood. But there can be only one simple and |

straightforward explanation of what took place, that it was the handiwork of the Almighty, whereby a sailor seasoned to crime came to himself in a far country and learnt and taught others to follow Christ. The Bible and Prayer Book in question were among the contents of the Bounty, which had been brought on shore before she was burnt. The Bible, it is stated, had been used by Christian and by Young before it came with the Prayer Book into John Adams' keeping. There is no indication that before ships began to call there were more than one copy of either book in the island, indeed, there are definite statements to that effect, and if this was so they may well have been on that account more potent in their influence on John Adams himself and more calculated to instil reverence into the minds of sons and daughters of native mothers as he taught them from this source alone. The clumsily-worded entry under date 28th February 1831 is one of much importance. "Arrived H.M.S. Comet Alex. A. Sandilands and Barque Lucy Anne. Colony of New South Wales. Government vessel. T Currey Master for the purpose of removing the inhabitants to Tahiti." It has been pointed out above that the Pitcairners' communications with the Pacific mainlands were rather with the nearer coast of South America than with Australia; but, as far as official relations were concerned, there was no British authority, other than Consuls, on the South American side, and the islanders' allegiance, so to speak, lay in the direction of Australia, the ships for this first migration coming from Sydney by order of the British Government. Pitcairn at the present day is within the "sphere of influence" of the High Commissioner of the Western Pacific, whose headquarters are at Fiji, of which he is also Governor. Succeeding entries in the Register record that on the 6th of March 1831 all the inhabitants embarked and sailed for Tahiti, and that they arrived at Tahiti on the 21st of March. It is stated, though not in the Register, that shortage of water on the island was the reason for the removal, and that the number removed, being the whole population, was 87, as against 40 when the Briton called in 1814. On the passage to Tahiti the Register chronicles a birth, but after arrival there was exceptional sickness among the incomers. The moral conditions of the place are said to have disagreed with the Pitcairners as much as its climate, and the result, as recorded in the Register, was |

that on the 24th of April, after barely a month's sojourn at Tahiti, a number of them, headed by John Buffett, sailed off in a small schooner, but owing to adverse winds were landed on what is styled "Lord Hood's Island." This is one of the Marquesas group; its native name is or was Fatuhuku, but it was named Hood Island by Captain Cook, who discovered it in the Resolution in 1774 and called it Hood Island after a midshipman of that name on board his ship, who was the first to see it. This midshipman was afterwards Captain Alexander Hood, a distinguished officer of the sea-going Hood family, who was killed in action. In regard to this island he was confused with his more famous kinsman Lord Hood, though Lord Hood was rather older than Captain Cook himself. Hence the name given in the Register. (The mistake has been perpetuated in the Pacific Islands Pilot, Vol. III, 1920 ed.) Here they remained till the 21st of June, when they embarked on a French ship, and on the 27th of June reached Pitcairn again, finding that in their absence the pigs had run wild and destroyed the crops. The rest of the community rejoined them at Pitcairn on the 2nd of September, having been brought back in the American brig Charles Dogget. Nobbs' name does not appear in connexion with this migration, and John Buffett seems to have been most to the fore. Buffett was described in Captain Beechey's narrative as "the oracle of the community." This would be at the time when the Blossom called at Pitcairn, in December 1825, before Nobbs came to Pitcairn. The Register shows that the loss of life which accompanied the move was terribly high, and this makes it difficult to criticise the shortness of the stay at Tahiti. At the same time the story illustrates what a source of trouble and expense on a small scale to the British Government have been these tiny groups of men and women, who have planted themselves in out of the way islands. On this occasion ships had been expressly sent from Sydney across the Pacific to carry the Pitcairners to a new and more accessible home in Tahiti. There everything seems to have been done with the active goodwill of Queen Pomaré for their comfort and welfare, but a month sufficed to set them on the move back again to their island, and the kindly action of the Government taken on their behalf was entirely thrown away. It will be noticed that for six years, 1832-7 inclusive, there |

are no entries whatever in the Register other than births, deaths and marriages, and that there is a total gap between the 5th of November 1833 and the 5th of April 1835. On the 28th of October 1832 there arrived from Tahiti an impostor named Joshua Hill. He claimed to have been appointed by the British Government as their representative at Pitcairn and he had had correspondence with Government offices and persons of standing which he was able to produce, when, as is shown in the list of shipping entries, Captain Fremantle, commanding H.M.S. Challenger, visited Pitcairn on the 10th of January 1833. Captain Fremantle, under instructions from the British Government, had previously brought the Challenger to Swan River and, landing on the end of May 1829, had taken possession for the British Crown of the whole Western side of Australia, leaving his name to be borne by the port of Fremantle. He was afterwards Admiral Sir Charles Fremantle, and must not be confused with another Captain Fremantle, who in command of the Juno visited Pitcairn in 1855 in connexion with the coming migration to Norfolk Island. The commander of the Challenger found that the Pitcairners had deteriorated through their sojourn at Tahiti, and had brought back drunken habits with them. Hill seems to have persuaded Fremantle that, whereas Nobbs and the other Englishmen were encouraging and abetting the evil, he himself had taken a stand against it. Fremantle therefore gave him his support, while by no means countenancing the arbitrary measures which Hill had taken or proposed to take. It is very difficult to follow exactly what subsequently happened and when, but Hill appears for a while to have wholly dominated and terrorised the islanders, and after the most outrageous proceedings to have practically enforced the banishment of the three Englishmen. All three left in the Tuscan for Tahiti on the 8th of March 1834. Apparently in about three months they returned, and picking up their families were carried on, in the case of Nobbs and Evans, and eventually of Buffett also, to the Gambier or Manga Reva Islands, a short distance to the north-west of Pitcairn in the direction of Tahiti, where Nobbs busied himself in teaching. The three were absent from Pitcairn for the inside of a year. The Hill régime would, unquestionably, have been very short-lived had it been possible for regular visits to have |

been paid to the island by H.M. ships. The correspondence which is printed in Brodie's Pitcairn Island and the Islanders in 1850 shows that the various authorities were by no means satisfied with what came to their ears and were anxious that a ship should go to Pitcairn and inquire, but that after the 10th of January 1833, when the Challenger called, it was not found possible to send a vessel until the visit of the Actaeon on the 12th of January 1837. Disillusionment with regard to Hill was then complete, for the Captain of the Actaeon, Lord Edward Russell, a son of the then Duke of Bedford, was able to give the lie to Hill's claim to be related to the Duke, and in the following December another Queen's ship, the Imogene, came with orders to deport him, and Pitcairn knew him no more. Brief but very important was the visit of H.M.S. Fly, commanded by Captain Elliot, on the 29th of November 1838. The Pitcairners, who now numbered ninety-nine in all, very earnestly represented to the captain the necessity of having some recognised chief authority in their community. They had experienced the want of it in the case of the Joshua Hill episode, and they had especially in view the dangers and difficulties caused when crews of whaleships who came on shore happened to be of the lawless and rowdy type, insulting the inhabitants and threatening violence to the women. The great majority of these whaleships were American, and an instance has been given above in which the commander of an American whaleship showed rare delicacy of feeling towards the unsophisticated islanders. Further, as all, or almost all, these vessels hailed from New England ports, they would, in most cases, in all probability have been manned by a good class of seaman. But there must also have been not a few exceptions, and of them Captain Elliot wrote in his despatch that they taunted the Pitcairners with having no laws; no country; no authority that Americans were to respect, for they denied that the islanders were under the protection of Great Britain, "as they had neither colours nor written authority." They had, however, as a matter of fact, a merchant Union Jack flying, which had been supplied by an English ship. In the absence of instructions the captain was in a very difficult position, but he considered it to be his duty to take some decided step, which would give protection to the Pitcairners while |

involving as little as possible the British Government, of whose intentions towards them he was ignorant. He therefore gave formal authority for "their election of a magistrate or elder to be periodically chosen from among themselves and answerable for their proceedings to Her Majesty's Government." The regulations for the purpose, which he drew up and signed on board his ship on the 30th of November, provided for the election of a magistrate or elder, being a native-born inhabitant of the island, on the 1st of January in each year by the free votes of all the native-born inhabitants, or five years residents, male or female, being over eighteen years of age. The magistrate was to be assisted by a council of two, one chosen by the votes of the assembly, the other by the magistrate himself. He was to report to the captains of Her Majesty's ships on their visits, his authority was to be obeyed by the residents on the island "under pain of serious consequences until he is superseded by the authority of Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain," and he was to take an oath that "I will keep a register of my proceedings and hold myself accountable for the due exercise of my office to Her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain or her representative." In addition to drawing up this and other regulations, Captain Elliot himself held a first election, having effect till the end of the year, he formally attested in writing that the elected magistrate had been sworn before him, and he provided a Union Jack to be flown as an ensign of British protection. Thus Pitcairn was in effect constituted a British colony, and when the Diamond Jubilee was celebrated in 1850, the Register spoke of the "anniversary of the settlement of the colony sixty years since." In the archives of the S.P.C.K., though not in the Register Book, is an address to Queen Victoria dated the 27th of July 1853, from the Pitcairn Islanders, signed on their behalf by their Chief Magistrate. It accompanied a specimen of their own workmanship for the Queen's acceptance,as explained in the following words of the address which are given as they stand: "At the suggestion of our worthy benefactor Rear Admiral Moresby we have ventured to present your gracious Majesty with a small chest of drawes of our own manifacture from the Island wood; the native name of the dark wood is miro; the bottoms of the drawers is made of the breadfruit tree; our means are very limited; and |

our mechanical skill also; and we will esteem it a great favour if your Majesty would condersend to except of it; as a token of our loyalty and respect to our gracious Queen." A previous part of the address was thus worded: "We humbly trust we may be allowed to consider ourselves your Majesty's subjects; and Pitcairns Island a British colony as long as it is inhabited by us in the fullest sense of the word. Several years since the Capt. of your Majesty's ship Fly took formal possession of our little Island; and placed us under your Majesty's protection; and if your Majesty's government would grant us a document declaring us an integral part of your Majesty's dominion; we should be freed from all fears (perhaps groundless) on that head; and such a gracious mark of Royal favour would be cherished by us to an exertion in the discharge of the various duties incumberent on British subjects." But it was not thought well to give any formal document of the kind, for the very good reason that it would have implied a doubt, where there was no doubt, with regard to the island being already a British possession and the islanders subjects of the British Crown. Her Majesty, in accepting the gift and the loyal address which accompanied it, referred to the donors as "her subjects on Pitcairn's Island." The visit of the Fly brought a more organized life among these primitive citizens, and it was initiated by one of the Captains of H.M. ships. All the world over, from generation to generation, those in command of the ships of the Royal Navy have added to protection of outlying bits of the British Empire, the functions of advisers, arbitrators, and friends in need of their inhabitants, applying kindly good sense and the proverbial handiness of the sailor to patient solution of endless petty problems, such as cause discord and discontent in small communities cut off from the outside world. With the entry of the 24th of March 1839 Buffett's journal ends. As a record of births, deaths, and marriages, it seems to have been fairly accurate and complete; and in as much as it did not purport to do more than chronicle family events, it must be forgiven for the patchiness of its general information. Nobbs, who at this point took over the journal, was obviously a better educated man than Buffett, and in his hands the journal became a narrative of a wholly different |

class. It is very much fuller, as much space being given now to one year as to a number of years before; and, in spite of occasional formal phrases and turns of expression, the contents are made interesting by clear consecutive writing and good arrangement, each year being summarised. Little comment will therefore be needed by way of elucidation. But it is obvious to those who study the original that various writers in addition to Buffett and Nobbs had a hand in the Register, there being great variety of handwriting as well as of expression. When Nobbs was in England, Mr. Holman became chief chronicler. Before this year 1839 ended, one of the Queen's ships, the Sparrowhawk, commanded by Captain Shepherd, arrived on the morning of the 9th of November, and stayed until the evening of the 12th. She had on board an ex-president of Chili, whom it seems Nobbs had known in his crusading days; the stay was longer than usual, but on all occasions when ships of the Royal Navy called, the proceedings were the same. This time on the 9th there were school examinations and prizes and presents; on Sunday, the 10th of May, the Captain and his officers attended divine service twice; on Monday several cases were submitted to the Captain for his decision; and on Tuesday he addressed the whole population gathered in the school house "on various subjects connected with their welfare." Thirteen ships are said to have touched at the island during the year, a greater number than ever before, but calls now multiplied. A little later, in 1845, the summary of the year gives twenty-five visiting ships, of which twenty were American, two French, and only one British, while in 1846, out of forty-nine ships that called, forty-six were American. In 1840 there are two entries which in a small way are rather surprising. "January 19th a Sunday School commenced." It would have been thought that a Sunday School had always been in existence from the beginning of John Adams' labours, but presumably it was only now that any teaching even of the Bible and Prayer Book began to be given on a Sunday. The second entry is that of the 2nd of May; it is the mention of a quarrel, carried to blows, between two of the elders of the island, one of them being the Englishman Evans. It seems singularly out of keeping with the traditional life of the community, and rather an unnecessary |

exposure by Mr, Nobbs of an unfortunate incident. In November a ship connected with the London Missionary Society called, the Chaplain or Missioner and the Captain of the ship spent two days on the island, and the entry in the Register reflects the theological colouring of the Society. The next year, 1841, was marked by a severe epidemic of influenza, which made the visit in August of H.M.S. Curacoa specially welcome, the surgeon of the ship devoting three days to the care of the sick. In September, a Tahitian woman, who had come to Pitcairn on the Bounty as the wife of Fletcher Christian, died at an advanced though uncertain age. According to her own account, she well remembered Captain Cook's first arrival at Tahiti. A reference to the Register for 1850 will show that when on the 23rd of January in that year the sixtieth "anniversary of the settlement of the colony" was celebrated, there was still one survivor of the Bounty, Susanna, also a Tahitian woman, who died on the following 15th of July. The year 1842 seems to have been uneventful. In 1843 took place one of the expeditions to explore Elizabeth Island to which reference has already been made, Eleven Pitcairners started for the purpose on the 4th of March, and came back on the 11th, bringing a very unfavourable report. Two more expeditions to that island are recorded in the Register as having taken place in August and November 1851, in either case in an American ship, and on the second occasion it seems to have been most thoroughly explored. It is noteworthy that the alternative name, Henderson Island, is not mentioned. This was, no doubt, for the reason that the Elizabeth was an American ship and the New Englanders must have put her name on the chart. In 1844, on the 28th to 31st of July, Captain Hunt of H.M.S. Baselisk made rather a prolonged visit to Pitcairn, during which the Register says that he "assembled the inhabitants, made some alterations and suggested others for the improvement of the moral and religious observances of the community," and "appointed a commercial agent." Meanwhile the surgeon of the ship vaccinated upwards of sixty of the islanders, but the vaccination turned out to be a complete failure. In January 1845 two of the Bounty's guns were retrieved from the bottom of the sea. One of them was found to have been spiked, but the other, in |

Mr. Nobbs' picturesque language, "resumed its original vocation, at least the innoxious portion of it." Unfortunately it was not an innoxious portion, for in 1853 the Register gives an account of an explosion of the gun when a salute was being fired, which had fatal consequences. In the first quarter of this year, 1845, there was another epidemic, and, reviewing the condition of the island, Mr. Nobbs reasoned that it was not, as was commonly supposed, a healthy spot, that the inhabitants suffered from diverse diseases, "and last but not least influenza under various modifications is prevalent." Five times within the last four years has "the fever been rife among us." That Mr. Nobbs had a considerable gift of graphic description is shown by his long account of a great storm in the night of the 16th of April, which swept the island, causing at one point a momentous landslide like an avalanche, and everywhere destroying fruit trees and foodstuffs on land and boats on the sea. A disastrous year ended with rumours of war. The chief event of the next year, 1846, was the completion and opening of a new church and school house, and in 1847 a shooting accident to a son of Mr. Nobbs. Fortunately one of H.M. ships called in time with a surgeon on board. No such aid, however, was available in the case of another accident in 1848, and, though Mr. Nobbs seems to have done all that could be done in the absence of expert surgical skill, the sufferer died. In the first half of 1849 one or more pages are missing from the Register, but the notice of the visit of Captain Wood in H.M.S. Pandora can be supplemented from the shipping list. The Mr. Buffett who was brought back by him from the Sandwich Islands, having gone there in the previous January, was evidently the father of the Buffett clan. The invitation from the British Consul-General in those islands to Pitcairners to migrate there seems to have borne no fruit. A second Queen's ship from Valparaiso and Callao, the Daphne, brought what the Register styled "the desiderata of the community viz a bull, cows and some rabbits," together with a large case of books from the S.P.C.K.; but something must have happened to the cattle, for in the Register in 1852 we are told that, when Admiral Moresby's flagship, the Portland, called in that year, it supplied Pitcairn, among many useful articles, with a bull and cow calves "for which we have long |

wished." It is recorded with emphasis that this year, 1849, was the first year in which two British ships of war had visited the island, and that in this year British ships outnumbered American among the callers, eleven against seven. Australian ships were now in evidence. During the months August to October the majority of the inhabitants, now numbering 155, were attacked by influenza of a severe type. The year 1850 was the Diamond Jubilee of the settlement of the colony, which was kept with loyal enthusiasm. Among the ships which called, American vessels once more outnumbered British, twenty-nine against seventeen. Among the British ships was a New Zealand ship, the Noble, bound from Auckland for California, five passengers from which, having been landed for the day on the 24th of March, and being allowed by the captain to spend the night on shore, were left behind, two of them being taken off by a ship which called on the 11th-12th of April, and two more by one which called on the 21st of April; what happened to the fifth is not clear. Of the two who secured passages on the 12th of April, one was Mr. Walter Brodie, who recorded his experiences in Pitcairn Island and the Islanders in 1850, published in 1851. There is no reference to these castaways in the Register, possibly through Mr. Nobbs' modesty, as they gave warm expression, with good reason, of their gratitude for the kindness shewed to them on the island; this will be found in the Shipping List. In 1851, beyond the visit to Elizabeth Island already mentioned, nothing worthy of note seems to have taken place. In 1852 no fewer than three of H.M. ships visited Pitcairn, and one of them was – for the first time – an Admiral's flagship. This was the Portland, bringing Admiral Moresby, a most warm and generous friend to the Pitcairners as a whole, and in particular to Mr. Nobbs. It was on this occasion that the Admiral took Mr. Nobbs and his daughter to Valparaiso on Mr. Nobbs' way to England to be ordained; and it has been already told that his place on the island during his absence was taken by the Rev. W. H. Holman. Mr. Holman subsequently presented to the Museum of the Royal United Service Institution several of the "Relics of the Bounty" which will be found there, including John Adams' prayer book. In 1853 Pitcairn was again visited by three of Her |

Majesty's ships. The first in point of time was a steamer, the Virago, the first steamer that had been seen by the islanders. She called in January and gave them a trip round their island. Her departure was the occasion of the fatal accident caused by the explosion of one of the Bounty's guns. In May Admiral Moresby brought back Mr. Nobbs and his daughter, and carried off Mr. Holman; and at the beginning of November H.M.S. Dido called, commanded by Captain Morshead. The Dido brought a stock of provisions in case the islanders should still be, as they had been, suffering from shortage of crops, and a full report of the visit is given in the correspondence connected with the Pitcairn Island Fund. It was a year of much sickness. With February 1854 the Register breaks off, owing to the dilapidation and consequent disuse of the book, which had been taken on board the Virago in Mr. Nobbs' absence and had been soaked in the process. Mr. Nobbs, it will be remembered, was now an ordained clergyman of the Church of England in receipt of a stipend of £50 per annum from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, and he began the year with a sermon in aid of the funds of that Society. The Shipping List is not carried beyond October 1853. By this time a Pitcairn Island Fund, which forms the subject of Appendix I, had been instituted in England, under a committee of influential men presided over by the Bishop of London. Mr. Nobbs' friend, Mr. Murray, of the S.P.C.K., was the Hon. Secretary of the Committee, the Society made a grant to it of £100, and a similar sum was subscribed by Admiral Moresby, ever to be relied upon in all that concerned the interests of his Pitcairn friends. They had multiplied greatly. In 1852, the last year for which a summary of the population is given in the Register, the total was returned as 168, males and females being exactly equal, as against 40 when the Briton came to the island in 1814. They had become, or were becoming, too many for the limited space, and arrangements were made to transfer them to Norfolk Island, which were carried out in 1856. They all migrated to the number of 194, though some of them only left Pitcairn with great reluctance and after much persuasion, and in two years' time one or two families began drifting back again. Conditions had greatly changed since, in 1823, the Cyrus imported Buffett and Evans to reinforce John Adams. |

The development of the Pacific whale fishery had, as has been abundantly shown, resulted in numerous visits of American whale ships, seeking fresh water, wood, vegetables and fruit, and this would account for the list of prices on page 97 being given in dollars. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought (until in 1851 gold was discovered in Australia also) a number of vessels en route to California from Australia and New Zealand. The captains of H.M. ships, not to mention lesser visitors, seem latterly, when they called, to have stayed on shore almost as a matter of course. The island, in short, lost, so to speak, its isolation and came into the world. But, after the effects of the unfortunate removal to Tahiti had worn off, the traditions of morality and religion, which John Adams had implanted, asserted themselves again under Mr. Nobbs' fostering care; and, with the opportunity of receiving the holy Communion, practically all the adults became communicants. It will be appreciated that the settlement on Pitcairn Island took place in a very interesting time in our religious history. The last years of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century were a fruitful time of evangelical effort, when Protestants generally seem to have realized in a far more wholesale manner than ever before that they had a call to go forth and preach the Gospel, and they found a wide and open field in the Pacific. Bible Christianity in simple and somewhat Puritan form was carried over the sea, and John Adams, with those whom he reared on the Bible and the Prayer Book, was all in harmony with it. So was one captain and another of the ships of the Royal Navy, as they came in contact with the Pitcairners in the middle years of the nineteenth century. This will be found illustrated by the wording of the note which Captain Wood of the Pandora entered in the List of Shipping on the 11th of July 1849, or a similar note entered by Captain Wellesley of the Daedalus on the 29th of January 1852. Very instructive, too, as to the type of Christianity presented to and absorbed by the islanders is Mr. Nobbs' entry in the Register on the occasion of the visit of the London Missionary Society's vessel on the 9th–10th of November 1840. But the Pitcairners, beginning with John Adams himself, were emphatically Prayer Book as well as Bible Christians, unswerving in loyalty to the Church of |

England. One of the books states that Joshua Hill, while upsetting their minds in other respects, was not able to undermine their Churchmanship. Such they were, interesting on the spiritual side, as from other points of view. But the story stands alone. Because it is so picturesque, it must not mislead us into falling in love with small and distant island communities, simply because they are small and distant. There is abundance of isolation or comparative isolation for necessary and useful purposes, but usually for limited periods only, at lighthouses, submarine cable stations and the like. The permanent continuance of small communities in out-of-the-way corners of the earth seems, on the other hand, to require justification rather than to command as a matter of course sympathy and approval. They are of scanty utility; they may at long intervals provide asylums for occasional castaways; the record of Tristan da Cunha testifies that they are fields for missionary self-sacrifice, as Pitcairn was for the devotion of Nobbs. But restricted communities inevitably tend to deteriorate, their claims or the claims made for them by their friends are disproportionate to their quantity and their quality; in effect, they are pensioners of the Government and the nation whose flag covers their home. Perhaps wireless and aviation may provide for them a future which will be a revised version of the past. |

PITCAIRN'S ISLAND

|

THE PITCAIRN ISLAND REGISTERFROM THE DESTRUCTION OF THE

|

|

Where are they now! The infatuated band Whose outrag'd feelings urg'd them on to crime? Proscribed, they wandered on from land to land; To Pitcairn's came and perished in their prime. |

|

What need I tell their hapless leader's fate (Slain by the hand of one he deem'd his slave) Save to the rash I would this fact relate, Nor mound nor marble marks his dubious grave. |

|

Their progeny – for these I hold the pen To mark their Birth into this fair abode; – When Love, to Marriage prompts the youthful train Or when by Death the soul returns to God. |

Births, Deaths, Marriages & Remarkable Family Events

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages & Remarkable Family Events

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

|

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

Summary.

Number of births, this year, eight; Marriages one; Deaths three. Thirteen ships have touched here this year: a greater number than ever arrived before in the same space of time. Fifty two scholars attended the public school. Number of inhabitants 106 – 53 of each sex. |

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

1840.

| |||||||||||||||

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

1840.

|

Births, Deaths, Marriages, & Remarkable Family Events

1840.

| |||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Marriages, Deaths) &.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &.

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

|

| |||||

|

|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

1848.

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &. &.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1849.

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &. &. [Apparently a page missing here. – Ed.]

|

1849.

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &. &.

|

1849

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

1849

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

Summary of the Year 1849.

|

1850

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

1851

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

1851

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c. &c.

| |||||||||

1852

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c. &c.

|

1852

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

1852

Births, Marriages, Deaths, &c.

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

This book has become so dilapidated from getting wet with salt water when taken on board the Virago at the commencement of last year, during my absence, that it is necessary to prepare a new hook by copying the contents of this into it and then continue from this date. It is my intention to send this Imperfection; to my well beloved friend the Rev. T. B. Murray, thinking it may serve to amuse him over his after dinner toast and water: though I think either my honoured friend or his sedate and most amiable spouse will find it difficult to translate many of the original autographs in the shipping list; and I think much of my own unrivalled penmanship, will be attended with similar difficulties. Pitcairns July 1854 [Signed] George H. Nobbs.

God help them all, the parents, the children, their maternal Aunt, the deaf gentleman and his wife, who I think is another Aunt; and if my recollection serves me aright there is also an Uncle whom I met once or more, and whom I suspect to be the author of a very pleasing eulogium on my appearance an peculiarities, in " Blackwood," and which was copied into an American paper and found the stay hither. Well, may their shadows never grow less and their happiness temporal and spiritual be ever on the increase. And may I have the pleasure of knowing it. [Signed] G.H.N.

|

FACSIMILE OF JOHN ADAMS' PRAYER.

|

Prices of Different Articles on

Pitcairn's.

17/2/34.

|

ARRIVALS

[being List of Shipping Entries]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Presents from Captain Jenkins Jones – and other Individuals

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Shipping List for 1843

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1846

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1847.

|

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1848.

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1849.

|

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1849

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1849

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1849

|

Shipping List for 1850

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1851.

|

|

|

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1852.

|

|

Summary of the Shipping List for 1852.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

SHIPPING LIST FOR 1853

| |||||||||||||||

|

APPENDIX I

The S.P.C.K. have in their possession the Records of the Pitcairn Island Fund Committee, consisting of three bound volumes which contain (1) the Minutes of the Proceedings of the Committee and (2) and (3) the Correspondence and other papers relating to its work.

The Pitcairn Island Fund Committee The Committee first came into existence in December 1852, and its original object was "to provide means for the outfit and passage home of the Rev. G. H. Nobbs, Chaplain of Pitcairn's Island, in December 1852, and for the supply of clothing, furniture and other needful articles for the inhabitants of Pitcairn. Towards this end a subscription . . . was raised by the friends of the cause; and the Authorities of the Admiralty afforded much valuable co-operation . . ." The first meeting of the Committee was on December the 3rd, 1852, at the Admiralty, under the Chairmanship of Bishop Blomfield (Bishop of London), the Rev. G. Nobbs being present. The Hon. Secretary of the Committee was the Rev. T. Murray (Secretary of the S.P.C.K.); the trustees were the Bishop of London, Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, Bart., and William Cotton, Esq. Those present at the first meeting were Sir Thomas Acland, the Hon. G. Waldegrave, Captain Fanshawe, R.N., Captain Inglefield, R.N., Arthur Mills, Esq., M.P., William Cotton, Esq., and T. T. Grant, Esq., F.R.S. (afterwards Sir Thomas Grant, K.C.B.). There is a list of names of distinguished persons who gave their patronage to the effort (among them being the Archbishop of Canterbury and Mr. Gladstone), and the list of subscribers is also given. The first Report Sheet (dated August 1853) of the work of the Committee says: – "The very scanty resources of Pitcairn's Island, containing a population of 170 persons, within a circuit of four miles and a half, with limited extent and imperfect means of cultivation, and the great need which existed of many articles of daily use, induced some friends of Mr. Nobbs, and of this interesting community, on the recommendation of Rear-Admiral Moresby, to raise a fund of moderate amount towards the passage and outfit of Mr. Nobbs and for the supply of such things as were most pressingly required by the inhabitants. Labourers' and carpenters' tools, a proper bell for the small wooden Church, Communion plate, medicines, two or three clocks, besides clothing of various sorts, some simple articles of household furniture and cooking utensils, together with stores and pro- |

visions were required; and it appeared likely that further supplies of some of these things would he required for some years to come. . . . In addition to the above, Mrs. Moresby collected and laid out in clothes for the islanders £20; Mrs. Nutcombe contributed and expended in a Gown and Surplice for the Rev. G. H. Nobhs £5; and a friend at Fulham presented silver Vessels for the Holy Communion, for use in the Church at Pitcairn." A Second Report Sheet was issued by the Committee (dated May the 29th, 1857), after the removal of the Pitcairners to Norfolk Island, which, after repeating the aims and objects of the Committee, continues: – "Although the attention of the Committee was, in the first instance, mainly directed to the above mentioned design, the members could not he indifferent to the progress of events in connexion with the state and prospects of the exemplary and amiable community, on whose account the Committee had been formed. "The islanders, having suffered from a fear of scarcity, caused by the failure of crops, and having, in May 1853, solicited the aid of Her Majesty's Government in 'transferring them to Norfolk Island or some other appropriate place,' the Government benevolently acceded to their proposition. This was notified to the Committee by letters from Herman Merivale, Esq., Under Secretary of the Colonial Department, December 1853 and April 1854. From that period to the present prompt and courteous communications have from time to time been received by the Committee from the Colonial Office, announcing the measures determined upon for the welfare of the Pitcairn community." Reference to the appended "Contents of the Committee's Books" will show that all the correspondence which passed between the Committee on the one side, and on the other the Colonial Office, the Admiralty, and the Lt. Governor of Van Diemens Land, as Tasmania was then called, with reference to these arrangements is still preserved. The Report continues: "Rear-Admiral Moresby, now Vice-Admiral Sir Fairfax Moresby, K.C.B., having arrived in England in 1854, after a recent visit to Pitcairn, the Committee were enabled with the greater accuracy to ascertain the condition of the island and the wants of the people. The Admiral had three times visited them and acquired the entire confidence and attachment of all the inhabitants. It will be remembered that to his generosity and good judgement was owing the voyage of their pastor and teacher Mr. Nobbs to England for Ordination in 1852." The Government was well advised in the matter of the transfer of the Pitcairn Islanders to Norfolk Island and in the steps taken |

for their welfare in that island by Sir William Denison, who had arrived in Van Diemen Land as Lt. Governor in 1847 and towards the end of 1854 was appointed Governor of New South Wales. "The measures of the Government having been finally matured for the conveyance of the people to Norfolk Island in the Spring of 1856, the Committee had opportunities of knowing the exceeding attention which was shown by all concerned, and which extended itself to the minutest details, for the successful issue of this remarkable movement. And the Committee must add that all the credit for the plan and execution of the transfer is due to the British Government. The preparatory step taken by the despatch of H.M.S. Juno, Captain J. S. Fremantle, R.N., to Pitcairn's Island, for the purpose of making enquiries, and giving information, was conducted by that officer with great kindness and discretion." Reference to the Minute Book and also to the Correspondence will show that an attempt was made to obtain permission for this visit of enquiry to be carried out "from the Pacific rather than the Australian station," so as to secure an officer known to and in possession of the confidence of the Islanders; and the Cockatrice, commanded by Captain Dillon, from Valparaiso, was first entrusted with the mission. Later it was found that the Cockatrice was laid up and would require to be specially equipped if employed, and under the circumstances the original "instructions for conducting the operation from Sydney have taken their course." The Report continues, "The vessel engaged for carrying the transfer into effect was the Morayshire, Captain J. Mathers; and during the whole of the passage the real interests and personal comforts of the people, young and old, of both sexes, were consulted in the most tender and scrupulous manner in all respects. Acting Lieutenant G. W. Gregory, of the Juno, performed his part of Superintendent in a manner which amply justified Captain Fremantle's choice of so intelligent and humane an officer for the task. Thus in the removal of 194 persons in an Emigrant Ship on a voyage of upwards of three thousand miles, occupying thirty five days, it does not appear too much to say, that no one could have desired a better kind of treatment for members of his own family. "The conduct of the respected Chaplain of Norfolk Island, the Rev. G. H. Nobbs, throughout the whole of this transaction, has confirmed the feelings of confidence and esteem which the Committee had previously entertained for him, and which he had earned by more than a quarter of a century's faithful and efficient service amongst the flock at Pitcairn. He not only attended to the religious wants of the voyagers, but all the medical duties likewise devolved upon him. These were of no |